This written account

was originally published in Radar: A Wartime Miracle Recalled

by Colin Latham and Anne Stobbs (1996).

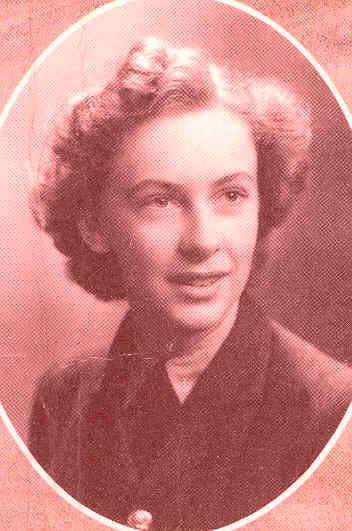

Anne Stobbs

Life on a UK radar station

was unique: I doubt if any other RAF or WAAF personnel experienced anything

quite like it. Most stations were very small and had comparatively few

officers and NCOs. In fact, 'you'll get no promotion this side of the

ocean' very much applied to the trade of radar! The vast majority of

mechanics and operators never got higher than LAC/LACW in rank; I doubt

if any employer ever got such a bargain when you consider the qualities

the RAF demanded.

It was nobody's fault that

we got no promotion thi side of the ocean (nor, for that matter, on

the other side of the ocean). There simply wasn't 'room at the top':

each station had it requirement of different ranks, and once they were

in situ, that was that.

One of the strangest aspects

of life on a radar station was the total division between tech. and

non-tech. personnel. A-site and B-site. A-site was where the radar itself

was, and B-site was where we all lived, and never the twain did meet.

They were usually at least a mile apart, in case of air attack, but

they were a million miles apart metaphorically speaking. No non-tech.

people were ever allowed anywhere near A-site, and this included all

non-tech officers - the adjutant, the WAAF admin officer, the RAF Regiment

Officer, etc. So you had a situation where everybody wearing a sparks

badge on their arm would be spending three-quarters of their lives within

a compound which some of their own officers and all the other clerks,

cooks, drivers, etc on the camp were forbidden to enter and new next

to nothing about. Sometimes this did not make for easy relations - it

was bound to be a difficult situation, especially for the WAAF admin

officers who were in charge of our welfare and discipline, but who probably

had a suspicion that we were happy to be out of their reach most of

the time. Which was perfectly true - we were!

Radar Operators

In spite of this, the atmosphere

on most radar stations was marvellous. Within such a small group of

people, everyone knew everyone else; and the even smaller groups which

made up the watches became very close-knit; friendships were formed

which often lasted for life. We also had good friendships with our own

mechanics, who looked after the equipment and shared our 'tea-swindle'

suppers on nightwatch. Marriages bewteen radar folk were quite common.

The level of hardship resulting

from the climatic conditions on most radar sites generated a terrific

comeraderie - you had to cope, so you did cope, but you were

glad of a willing pair of hands to help you.

On most stations, some of

this hardship, plus the effects of working a watch system, were counteracted

by organising little concert parties and shows. All the local talent

was pressed into service, and a lot of fun ensued, for both the performers

and the audiences. There were always camp dances too, and liberty runs

into the nearest town, with ahppy sing-songs in the back of the transport

of the way home.

On watch we could relax in

the rest rooms, where we all apent 'off the tube'. One hour on was the

norm for operators; somebody had decided, quite rightly, that an hour

at a time of staring into a CRT was enough for your eyes and your powers

of concentration. So some of the watch was always in the quite comfortable

litlle rest room, brewing up tea, chatting, knitting, reading, writing

letters and, on nightwatches, frying up eggs and bacon to keep body

and soul together.

Nobody who worked on radar

is likely to forget that miserable feeling around two in the morning,

when your body was at its lowest ebb, crying out to be asleep, yet having

to force itself to stay awake. The atmosphere, especially in an underground

opes room, was really awful - dry and soporific, with incessant humming

from electrical apparatus.

And yet there were many compensations,

not least the feeling of intense pride we all had from doing a difficult,

technical and highly-secret job. Everybody on radar felt that they were

doing the job and wouldn't have done any other. And as far as

one knows, every single soul kept their mouths shut throughout the war

about what they were doing. (Even within one station, where there were

different radars, one didn't discuss what one was doing with people

working on different radar).

This special ethos was quite

amazingly rekindled fifty years later, when we started the big reunions.

700-strong or more, with ex-radar folk coming from Canada, the US, New

Zealand, South Africa - all suddenly re-experiencing that feeling of

pride in ourselves and in the job we had done all those years before.

The reunions also served

as a reminder of some of the enchanting names of the radar stations,

which will surely ring a nostalgic bell with all who ever them, either

through serving on some of them or talking to them on the intercom.

Most of them were names of tiny villages or simply local areas known

by those names. How about Tilly Whim, Stoke Holy Cross, High Street,

Stenigot, Gibbet Hill, Canewdon, Truleigh High, School Hill, Windyhead

Hill, Burifa Hill, Sligo, Brandy Bay, Rosehearty, Ottercops, Bawdsey

- names to bring the memories back?

![]()